Google's Gemini AI still needs trainer-wheels

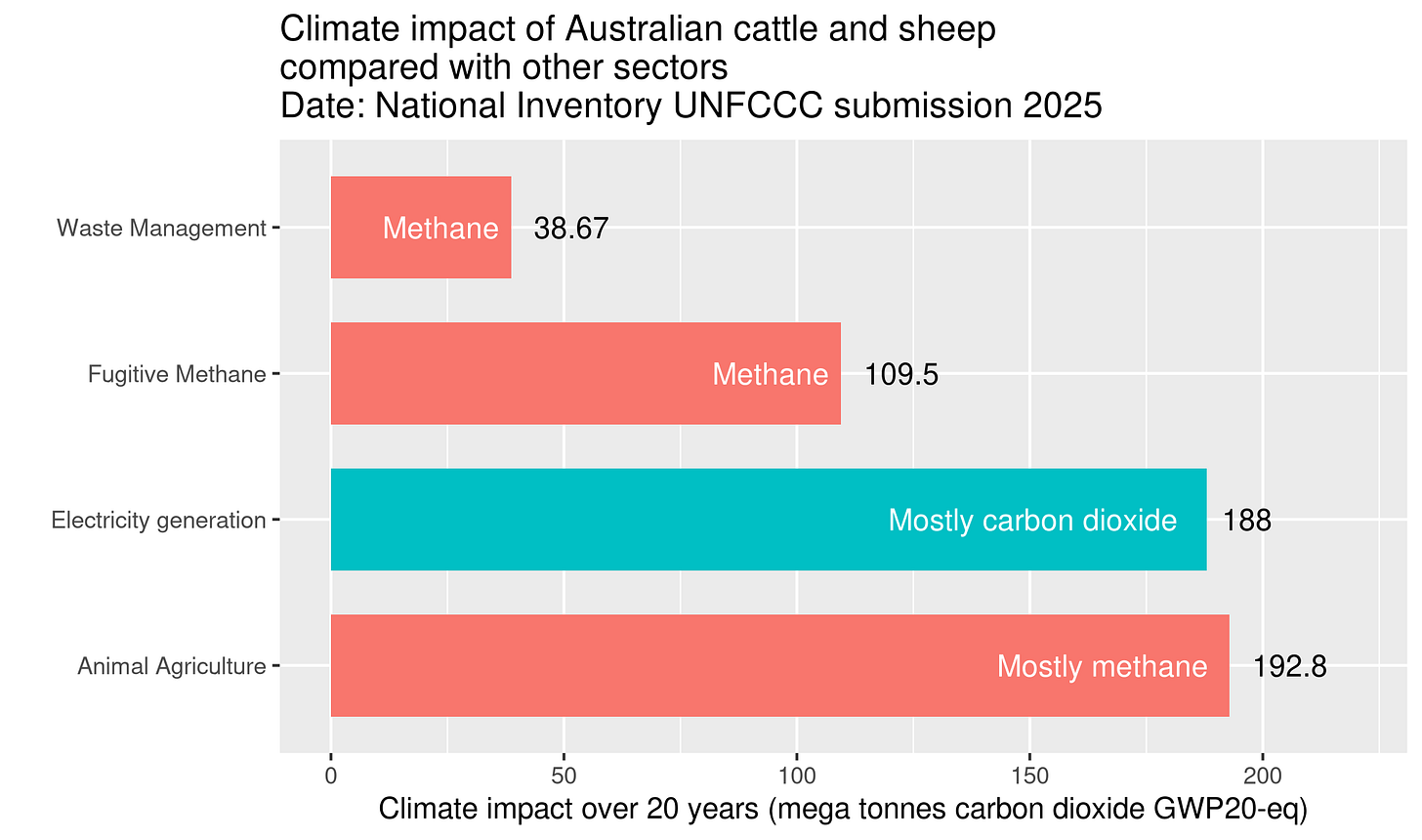

In writing a submission on greenwashing for a Senate inquiry, I spent time with Australia’s National Greenhouse Gas Emissions inventory. I was calculating just how our animal agriculture emissions compared with that or our electricity generation emissions. Here’s the result.

It’s not rocket science. You just download Australia’s greenhouse inventory from the UNFCCC website. Then you look up a couple of tables, multiply the weights of the various gases by a factor intended to normalise the numbers so that you can add them together (more on that later). The result is in the chart above.

The take-home point is that animal agriculture is a bigger climate problem than all our fossil-fuelled power plants. That didn’t surprise me. I’ve calculated this number quite a few times since 2008, when I first understood enough climate science to realise that methane was a really big deal.

But what does Google’s Gemini say?

So then I thought I’d see how Google’s Gemini coped with answering a few questions about Australia’s greenhouse emissions.

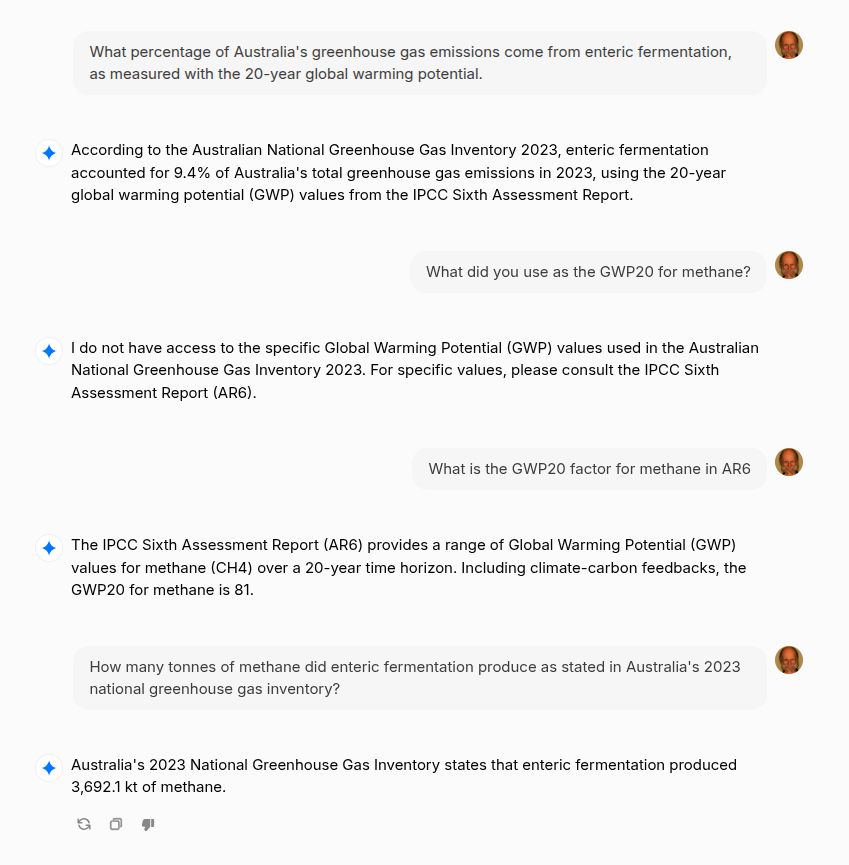

Here’s the dialogue. Beware. It’s mostly just “confident” bullshit. Which doesn’t make it much different from anything that a politician might say about this particular topic. I had to put quotes around the confident word, because an AI doesn’t have confidence, or an agenda, or any other human characteristic.

Let’s take the last question first. I asked for a very particular number; not an opinion, not something from some newspaper article; but an exact number from a precisely specified report; Gemini got it wrong. Its answer wasn’t even close.

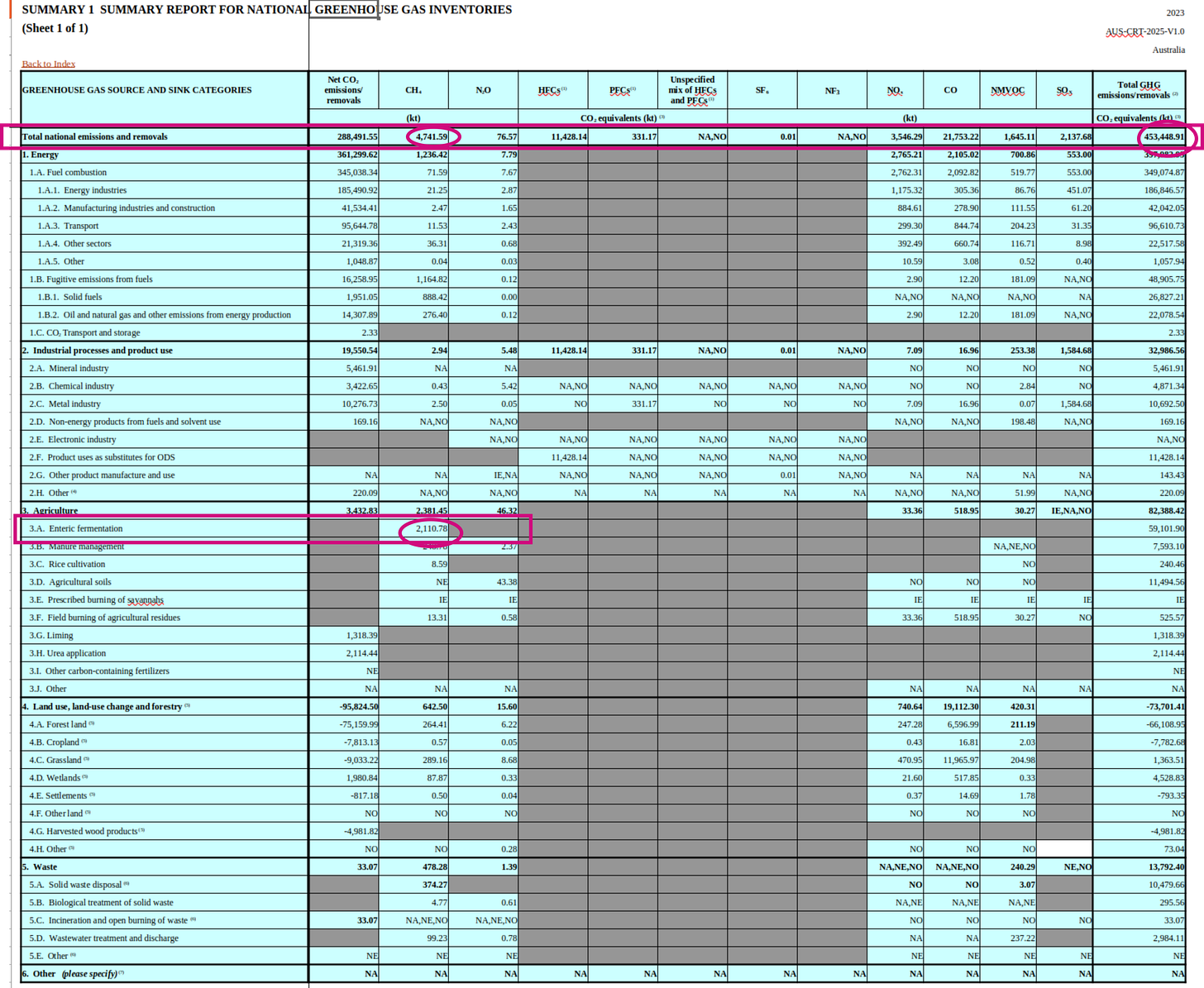

Here’s the table with the actual number.

Check the row marked “Enteric fermentation”, it’s the second highlighted row. The number is 2,110.78. Look up the top and you can see that the units are (kt). Gemini got it wrong. The number 3,692.1 doesn’t appear anywhere in the document. The enteric fermentation figure has never been so high, not since people started estimating it in 1990.

Now let’s work backwards through the preceding questions.

Gemini successfully identifies the GWP for the 20 year time horizon (aka GPW20); and rounds it to the nearest integer. Excellent. It misses the fact that the IPCC report it mentioned gave two numbers for the GWP20, depending on whether the methane contained new carbon (ie, from a fossil fuel source), or old carbon (ie from cattle or a swamp … so called “biogenic” methane). But since the two numbers are very close, that’s no big deal.

Moving on up. The previous question was about the factor it used to estimate the GWP20 for methane in its previous answer. It produced a number but didn’t “know” the factors that were required to get that number. That should alert you to the fact that this is an AI and not someone with a solid understanding of how the numbers in the report get calculated.

Now we arrive at the start. I asked a question about a number which varies from year to year, but I didn’t put a year on it. Gemini assigned a year and produced a number; the wrong number.

If you want to derive the percentage of Australia’s emissions which come from enteric fermentation using the GWP20 figure, then you need to understand that the total figure was produced using GWP100. That’s the figure circled in the first highlighted row, at the top right. Happily, you can easily calculate the total figure using the GWP20, because all you need to do is to multiply the 3 figures for carbon dioxide, methane and nitrous oxide by their GWP20. That’s not exactly right because it ignores the other gases HFC’s and the like. But it will be close. Knowing when you can ignore trivialities is a pretty sophisticated skill. My first university level physics lecturer was astonishing at this. He could calculate some incredibly complex numbers using rough estimates and ignoring stuff that didn’t matter. Moving on … then you can use the enteric fermentation figure (multiplied by the GWP20) and divide by the total. This is elementary high school arithmetic.

Gemini’s answer of 9.4% isn’t even close. The actual number is about 24% (using the simplied method above) and 26% if you don’t ignore the details ( add in the HFCs, etc.).

Why did Gemini screw up?

It’s incredibly hard to believe that an AI works the way it does. Play around with them for a couple of hours and you’ll be mightily impressed. They can fool you into thinking they know stuff. This makes them very much like people; who can also fool you into thinking they know stuff, when they don’t.

So, how do AI’s work? If you want a moderately long and stunningly beautiful explanation, then check out the “Neural Network” playlist on YouTube by Grant Sanderson.

The short explanation is that they work out probabilities of every possible word in their dictionary coming after the string of words in your question. Based on looking at a whole collection of examples. Then they pick one near the top of the list. They add a little randomness, so they don’t always produce the same answer. But that’s it. They just keep doing that. Over and over again. So, why do they stop? That’s far too complex to explain and a topic of considerable research.

There are all manner of enhancements to this basic process. Like generating three responses and then using those to generate a forth, which you then present as if it was the first.

If you train them on a bunch of maths proofs, then they’ll get extremely good at producing maths proofs. Extremely good, in this case, means better than most skilled people.

Nobody should believe my explanation without double-checking. The idea that such one-word-at-a-time prediction could resemble intelligence is bizarre. But there is a little deja vu about this. In the world of fractal mathematic, extremely simple rules can yield unpredictable complexity and beauty.

So the screw up shouldn’t be surprising

Gemini, like other models, is trained by sucking in a vast amount of information from the internet. I haven’t been able to find the source of the 3,692.1 number, but maybe it’s out there somewhere. I did a post about AI and radiation mistakes a little over 12 months ago. It was a broadly positive post. The finding was that, unlike humans, the potential for AI to dig deeper in response to probing questions was incredibly useful. Humans tend to dig in, defend their position and are necessarily slow to assimulate new information; especially in response to being challenged. But this time around, I’m more perplexed and anxious. The confidence of Gemini in claiming a given report contained a very precise number is disturbing. Do humans do this? They might say, “I think the report said something like 3,000 kt”, but when a human says an exact number, we are (at least I am) very tempted to believe they know what they are talking about. We love confidence. We vote for confident people who make grandiose claims, we invest savings with them. I hope this post gives people pause for thought. Do your due diligence on AI claims.

And do even more due diligence on confident claims from people.