Deep-sea mining (Part II): Biodiversity and the CCZ

This is the second instalment of a critique of the ABC Four Corners episode on deep-sea mining, Race to the Bottom; Part I is here

Apologies for not yet reaching the critique proper, but I’m still digging the footings; I want a deeper foundation for the analysis.

Let’s continue by comparing the size of the proposed mining area in the Clarion–Clipperton zone (CCZ) with other areas of the planet we exploit. I’ll express all measurements in millions of square kilometres.

The area of the CCZ is close on 6 million km². As of Sept 2025, 21 blocks of 0.088 million km² have been allocated to contractors; totalling about 1.8 million km²; that’s about the size of Queensland, or Alaska. These are designated as “exploration” areas; and amount to about 30% of the CCZ.

In comparison, global land mining areas are tiny.

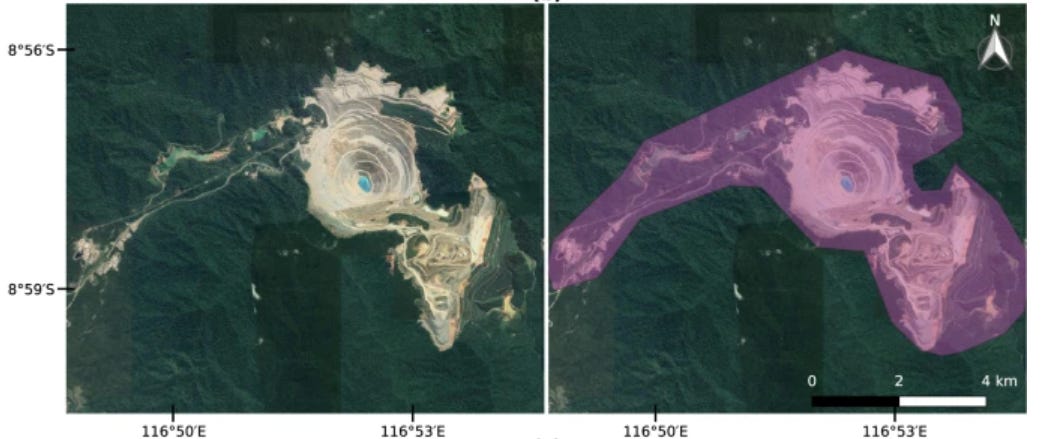

A 2020 mapping study measured over 6,000 mine sites and came up with a total of 0.06 million km². To be included in this study a mine needed to be active during the past two decades; it includes coal and all metals and industrial minerals; but not, as far as I could tell, sand and aggregates. Here’s an image showing how they used mapping to measure the extent of mines. This is the Batu-Hijau copper and gold mine in Indonesia.

Biodiversity comparisons: CCZ vs Coral Reefs vs Tropical Forests

The CCZ hasn’t been extensively studied, but estimates put the total number of animal species at something less than 7,500. There are no plants on the sea-floor, they need sunlight and there is none at the depth of 4,500 metres where the mining is proposed.

Bird watchers often carry checklists and tick birds off as they see them. Is there a 7,500 species check list for the CCZ? No. It’s a theoretical estimate. The number of species actually “collected”, meaning killed and examined, is very much smaller. I don’t have a number but it is tiny.

So how is this figure of 7,500 estimated? Suppose you take a sample of critters from the ocean floor in the CCZ and count the number of different species. Then take another sample and see how many of the same species you have and how many new ones. Do this a bunch of times and apply some reasonable statistical methods and you can get an estimate of what you might find if you could sample the entire area. There are a few different statistical methods but they all come up with similar numbers.

The global area of coral reefs is about 0.35 million km²; much smaller than the CCZ. So the CCZ is ~17 times bigger than the global area of coral reefs. But that tiny coral reef area supports an estimated 0.55 to 1.3 million species. Of these species, an estimated 9% have been named. So, again, the 0.55 to 1.3 million range is an estimate, made using reasonable statistical inference.

So there are between 1200 and 3000 times more species of critter per km² on a coral reef than there are in the CCZ.

Keep this in mind when people claim (as they did in RTB) that the CCZ biodiversity is “mind blowing”. Some minds are more easily blown than others.

In later sections, I’ll discuss the species diversity of the CCZ in more detail. But, unless you are a taxonomist, someone familiar with the classification of critters the rest of us have never heard of, you’ll have a tough time contextualising this figure of 7,500 species.

Perhaps you have in mind the multitudes of fish on a reef or birds in a forest. In tropical forests, for example, there are 21,092 vertebrate species. For many people, vertebrates dominate their imaginings when they think of animals. But there are very few vertebrate species in the CCZ; hundreds at most. Most of the 7,500 species are worms or insects. When people fall in love with forests in nature documentaries, it’s the familiar animals which captivate; mammals, reptiles, amphibians and birds, the vertebrates; plus, perhaps the butterflies.

The CCZ is very different. It’s full of things people move past without giving a second glance if walking in a rainforest or snorkelling on a reef. Defenders of the CCZ are leveraging the emotional buzz associated with the word “biodiversity” while ignoring that biodiversity in the CCZ has a very different meaning.

Why different? Suppose you are fascinated by viruses, you may know that there are tens to thousands of millions of viral particles in a handful of soil. Are you worried about protecting this biodiversity? You should be concerned about soil health, but campaigns to stop people digging holes because they might kill viruses would be met with derision. The biodiversity of viruses, worms and vertebrates are not all equal. We have to make value judgments about what matters.

In any event, the biodiversity of the CCZ just isn’t rich compared to that of coral reefs or tropical forests. In many parts of the world, coral reefs are mined for limestone and building materials. We also mine tropical forests. Indonesian nickel mines, for example, have expanded from 74,000 tonnes a year in 1998 (about 6 per cent of global production) to 2.2 million tonnes a year in 2024 (over 60% of global production); all of it from the destruction of tropical forests.

Nickel is plentiful in the poly-metallic nodules of the CCZ and could, if the price was right, prevent further tropical forest destruction.

While the CCZ is large and not well explored, there is already a set of protected “Areas of Particular Environmental Interest” (APEI). A 2021 study looking at 3 such sites, found substantial variations in the density and types of species between the areas. On land, even non-experts can easily see differences between deserts, scrub, wetlands and rainforests. In the CCZ, you need to count critters and calculate F-statistics.

Large modern Western mining companies are used to working around restrictions like APEIs. They are sensitive to their public image. But the longer the CCZ stays off limits, and the more regulatory roadblocks that are set up to slow them down, the more damage will be done to tropical forests by mining companies with fewer scruples.

In September a moratorium on the operation of the Raja Ampat nickel mine in Indonesia was lifted. You can see the images from Greenpeace of damage allegedly caused by this mine in an offshore reef. Such allegations have been frequent during the expansion of Indonesian nickel in the past 20 years. In 2023, 18 workers were killed and 46 injured in an explosion at a nickel refinery in Indonesia.

Would mining in the CCZ displace Indonesian nickel?

Mines everywhere are quickly mothballed when a cheaper alternative emerges. The vertical integration in Indonesia of mines with refineries close by makes the resulting nickel very cheap. Global markets have shown little concern for the tropical forest impacts. But you can be sure that if CCZ nickel was cheap enough, those markets would react in a heartbeat.

In Part III, I’ll expand the kinds of land-use comparisons. Environmentalists are very selective in what they fight for. The Australian environment movement, in particular, is often said to have been born in the fight for Kelly’s Bush in the early 1970s. The first “Green Bans” in the world were enacted to protect 7 acres of bush in Sydney’s rich North Shore. The Builder’s Labourers Union joined the fight led by one Jack Mundey. Contemporaneously, Bob Kleberg of King’s Ranch in Texas bought and bulldozed 50,000 acres (20,000 hectares) of virgin rainforest in North Queensland to run cattle. By the time of the famous protests at Kelly’s Bush, the protesters may well have been using “rainforest beef” on BBQs to raise funds to save their precious 7 acres. In the past 50 years, not much has changed, environmentalist all over the world are still very selective in what they fight for.